Introduction

Concepts in spaces

What does it mean to "learn vowels"?

Peterson and Barney (1952, p. 182)

Spaces

What are vectors?

3Blue1Brown on vectors:

In truth, it doesn’t matter whether you think of vectors as fundamentally being arrows in space that happen to have a nice numerical representation, or fundamentally as lists of numbers that happen to have a nice geometric interpretation. The usefulness of linear algebra has less to do with either one of these views than it does with the ability to translate back and forth between them. It gives the data-analyst a nice way to conceptualize many lists of numbers in a visual way, which can seriously clarify patterns in the data and give a global view of what certain operations do. On the flip side, it gives people like physicists and computer graphics programmers a language to describe space, and the manipulation of space, using numbers that can be crunched and run through a computer.

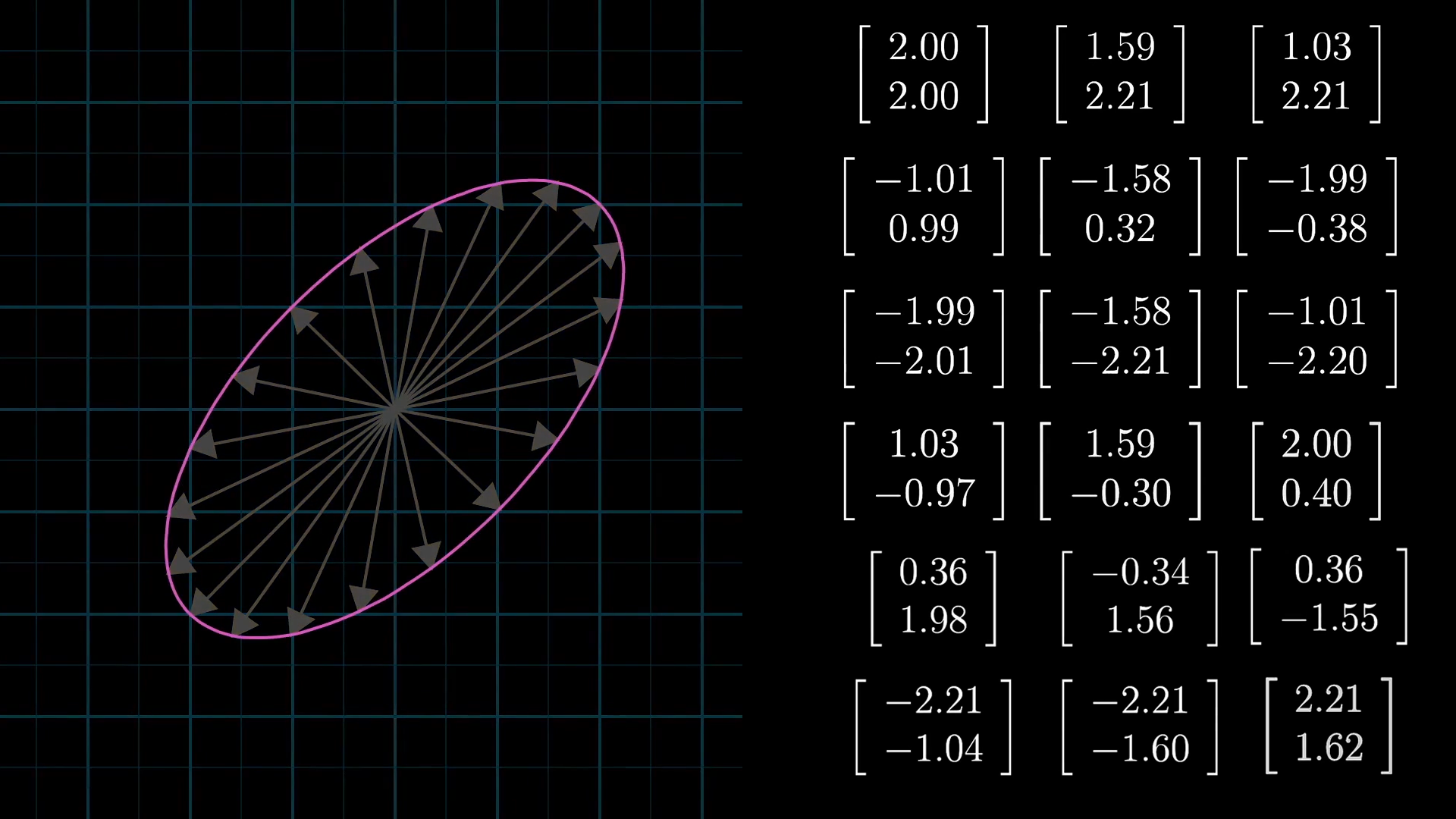

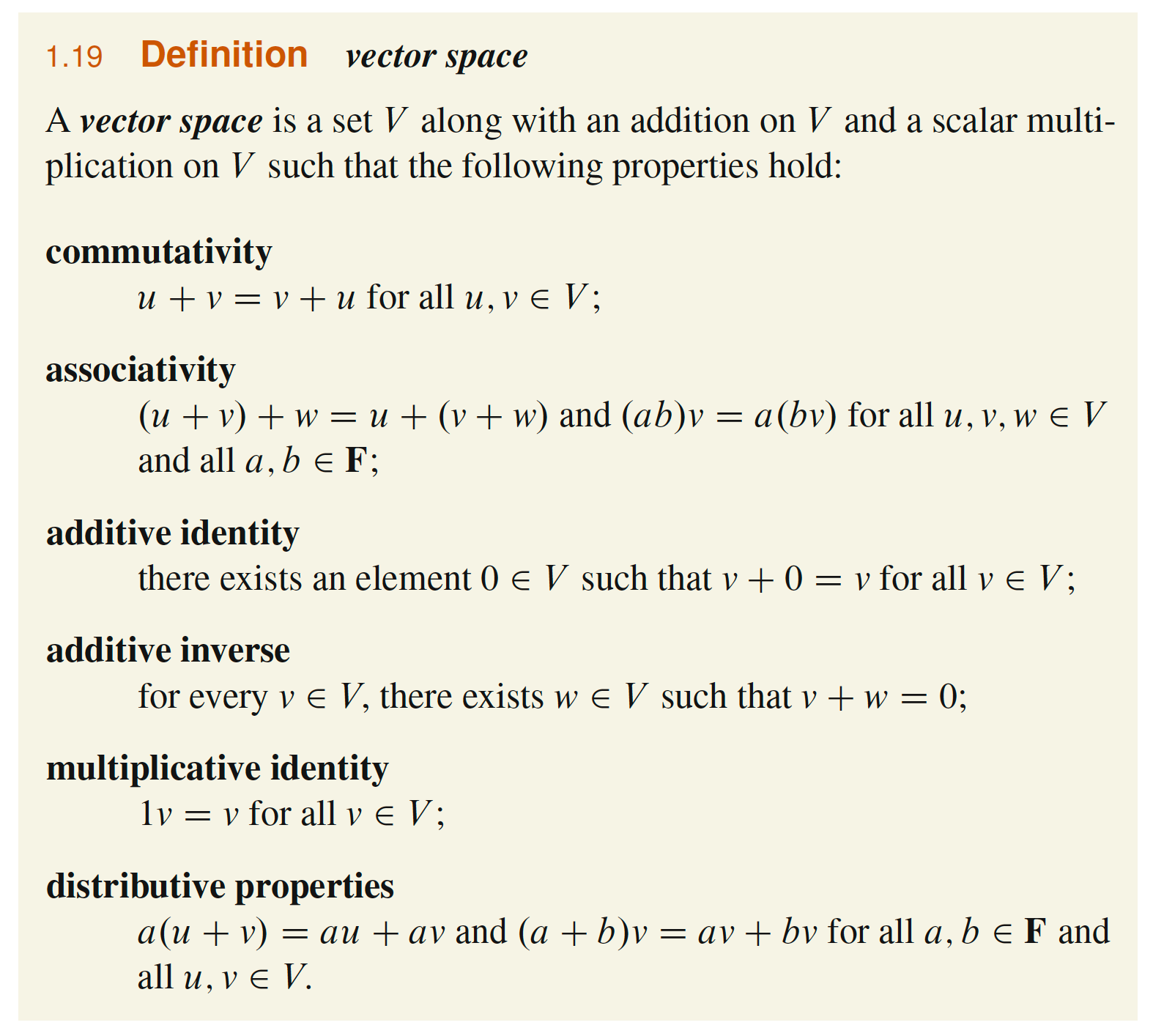

Let's take this still of geometric and numerical perspectives for vectors from 3Blue1Brown's lesson on vector spaces. What does this remind you of, from thinking about phonetic spaces?

What's that "graph paper" representing? It's

The set

(What's the definition of

How do we generalize to higher dimensions? From Axler (2015, Definition 1.8):

Suppose

is a nonnegative integer. A list of length is an ordered collection of n elements (which might be numbers, other lists, or more abstract entities) separated by commas and surrounded by parentheses. A list of length looks like this: Two lists are equal if and only if they have the same length and the same elements in the same order.

So to generalize to

Addition and multiplication on vectors

Relate these to phonetic spaces!

3Blue1Brown vector addition animation:

3Blue1Brown vector scaling animation

That's all you need to define a vector space!

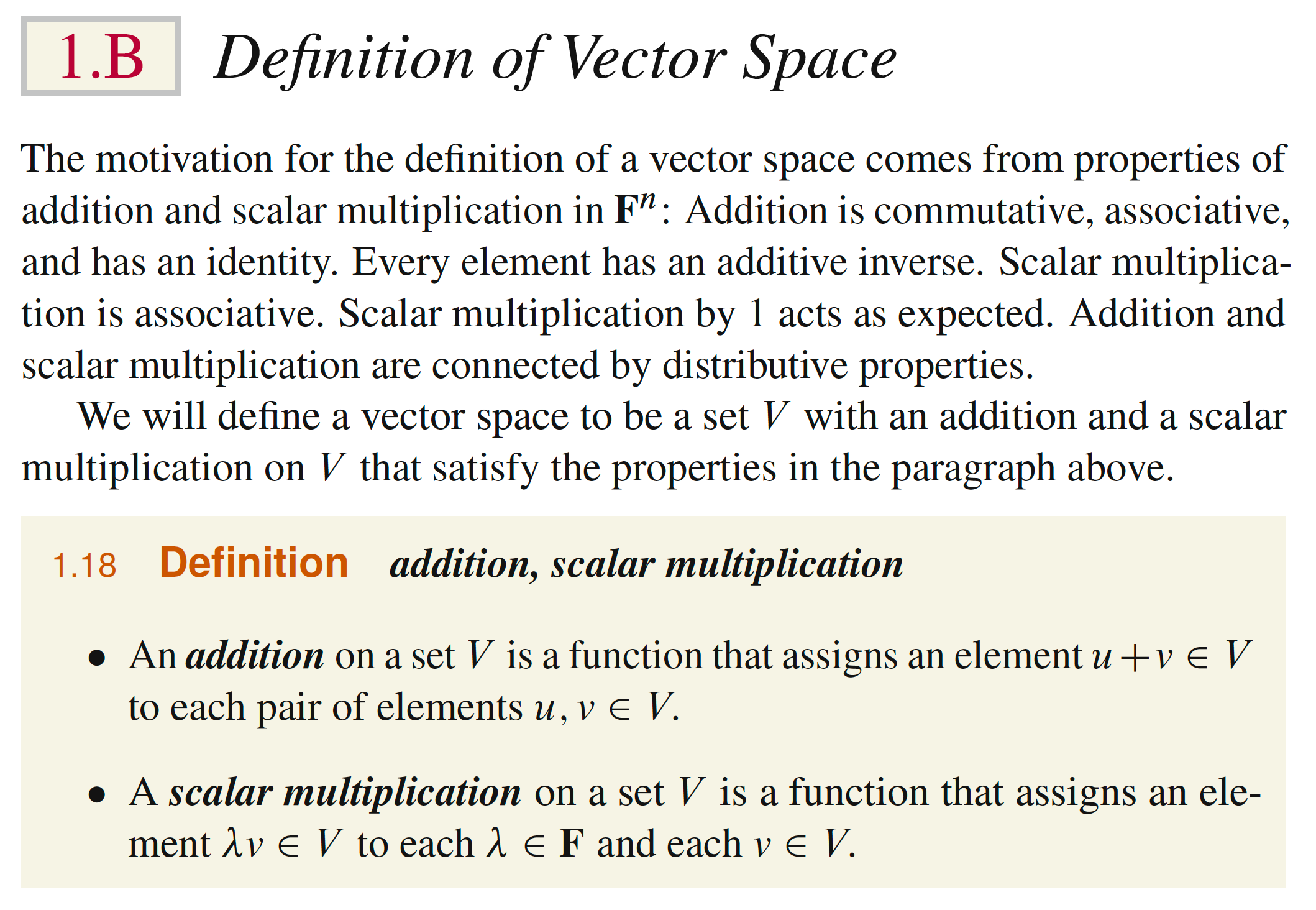

More formally, from Axler (2015) p. 12: (note: you can substitute out

And once you have a vector space, you can introduce the idea of basis vectors.

A still of basis vectors from 3Blue1Brown's lesson on linear combinations, span, and basis vectors.

Vector-ish spaces: basis functions

The same simple, geometric intuitions you have about vectors apply to "vector-ish" things like functions. These intuitions form the essence of approaches to scientific understanding of spaces that phonological concepts live in!

Here's a still from 3Blue1Brown's lesson on abstract vector spaces

Moving from a waveform to a spectrum (animation from Lucas Vieira) is the decomposition of the waveform into sines and cosines (Fourier basis)!

Interactive Fourier series demo

Animations from Gavin Simpson's GAMs webinar repo.

You give me a squiggly curve over [0,1]: some function

I can build it for you from a basis set of splines, i.e., a linear combination of spline functions!

Learning concepts: defining the learning problem

From Osherson et al. (1985) p. 8 Systems that Learn:

Learning typically involves

- a learner

- a thing to be learned

- an environment in which the thing to be learned is exhibited to the learner

- the hypotheses that occur to the learner about the thing to be learned on the basis of the environment

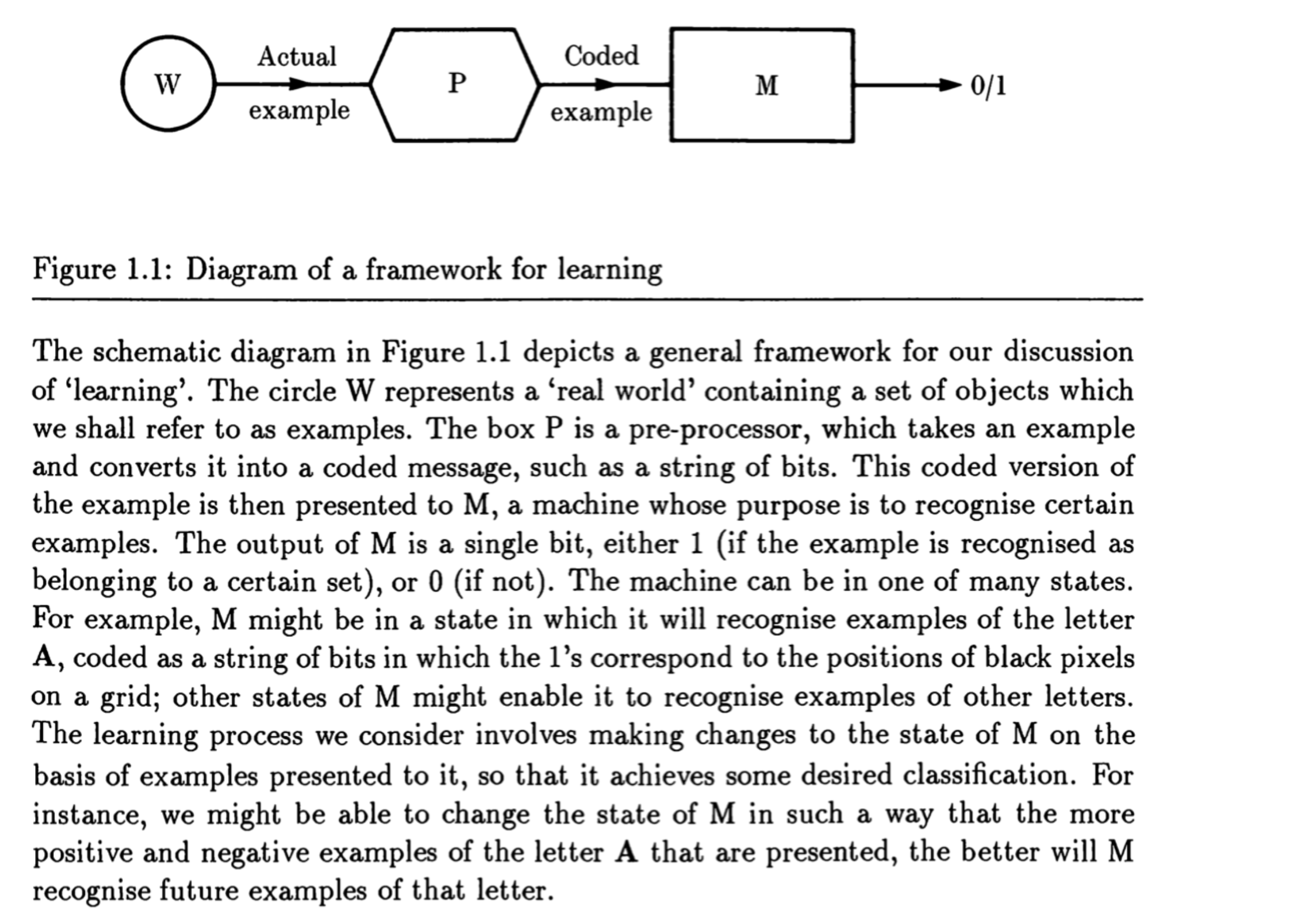

See also Anthony & Biggs (1992, p.1) on learning from examples, especially the distinction between the actual example and the coded example.

Niyogi (1998, p. 3-7): informational complexity of learning from examples

"...if information is provided to the learner about the target function in some fashion, how much information is needed for the learner to learn the target well? In the task of learning from examples, (examples, as we shall see later are really often nothing more than

pairs where and ) how many examples does the learner need to see?

"Things to be learned": the concept class

"an environment in which the thing to be learned is exhibited to the learner": via the access of the learner to examples

"the hypotheses that occur to the learner about the thing to be learned on the basis of the environment"

"The learner operates with a set of hypotheses about reality. As information is presented to it, it updates its hypothesis, or chooses among a set of alternate hypotheses on the basis of the experience (evidence, data depending upon your paradigm of thinking). Clearly then, the learner is mapping its data onto a "best" hypothesis which it chooses in some sense from a set of hypotheses (which we can now call the hypothesis class,

For a particular concept

From Niyogi (1998, p. 10) on factors affecting the informational complexity of learning from examples:

but see alternative perspectives (!!) ... Mumford & Desolneux (2010, p. 4)

"To apply pattern theory properly, it is essential to identify correctly the patterns present in the signal. We often have an intuitive idea of the important patterns, but the human brain does many things unconsciously and also takes many shortcuts to get things done quickly. Thus, a careful analysis of the actual data to see what they are telling us is preferable to slapping together an off-the-shelf Gaussian or log-linear model based on our guesses. Here is a very stringent test of whether a stochastic model is a good description of the world: sample from it. This is so obvious that one would assume everyone does this, but in actuality, this is not so. The samples from many models that are used in practice are absurd oversimplifications of real signals, and, even worse, some theories do not include the signal itself as one of its random variables (using only some derived variables), so it is not even possible to sample signals from them."

"Fn 1 immediately following: This was, for instance, the way most traditional speech recognition systems worked: their approach was to throw away the raw speech signal in the preprocessing stage and replace it with codes designed to ignore speaker variation. In contrast, when all humans listen to speech, they are clearly aware of the idiosyncrasies of the individual speaker’s voice and of any departures from normal. The idea of starting by extracting some hopefully informative features from a signal and only then classifying it is via some statistical algorithm is enshrined in classic texts such as [64]."

- It's important that we make a distinction between the "actual example" and the "coded example"! Similarly, between "input" and "intake", e.g., Lidz and Gagliardi (2015):

"This model of the language acquisition device has several components, which we explore in more detail below. The input feeds into a perceptual encoding mechanism, which builds an intake representation. This perceptual intake is informed by the child’s current grammar, along with the linguistic and extralinguistic information-processing mechanisms through which a representation from that grammar can be constructed (Omaki & Lidz 2014). To the extent that learners are sensitive to statistical–distributional features of the input, as discussed below, that sensitivity will be reflected in the perceptual intake representations.

The developing grammar contains exactly those features for which a mapping has been established between abstract representations and surface form. A learner’s perceptual intake representation does not contain all of the information that an adult represents for the same sentence. If it did, then there would be nothing to learn (Valian 1990, Fodor 1998). What it does contain, however, is information that is relevant to making inferences about the features of the grammar that produced that sentence. This perceptual intake feeds forward into two subsequent mechanisms: the inference engine and the production systems that drive behavior."

Let's think more about each of those pieces in setting the learning problem. Can you think of others?

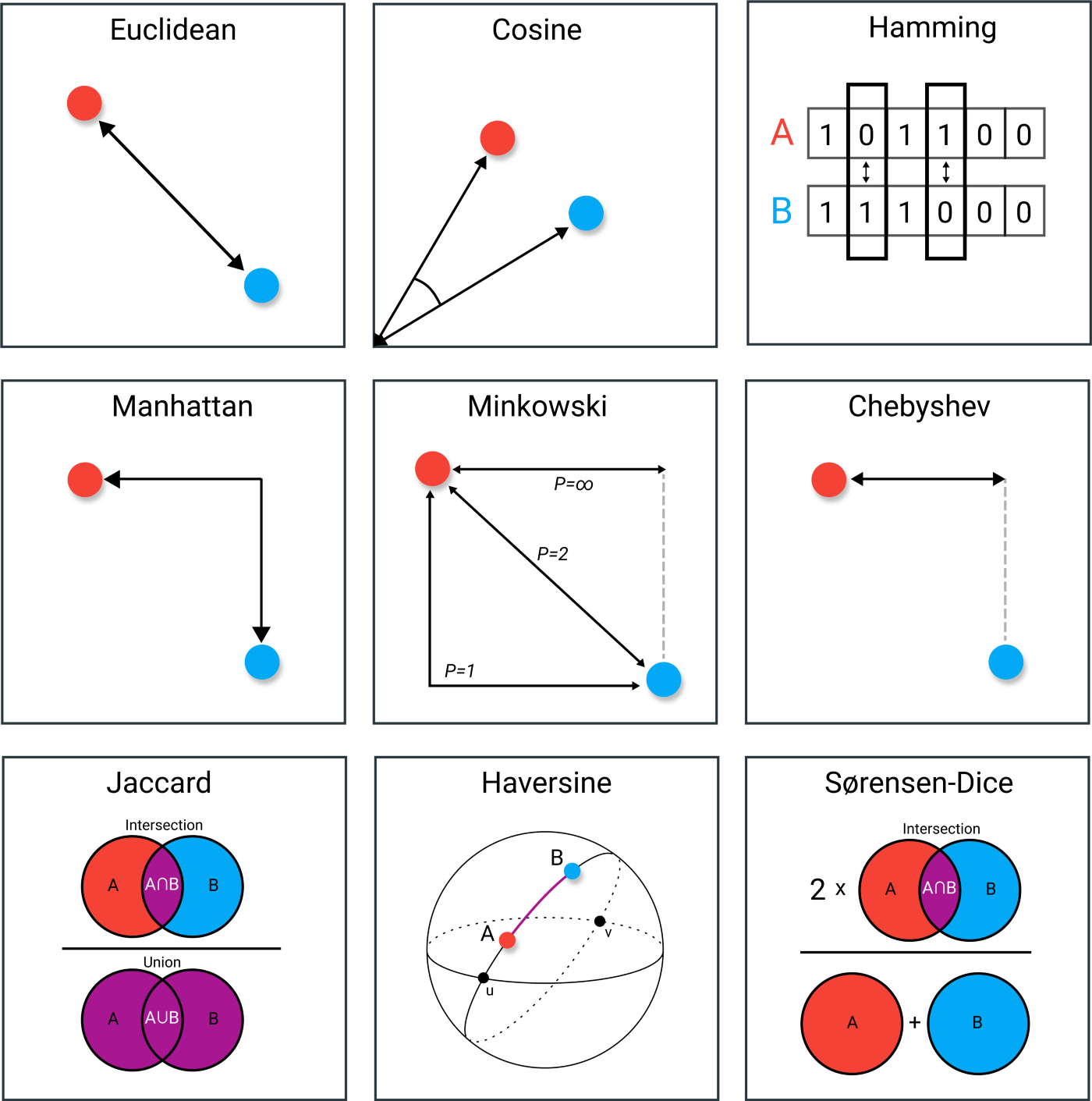

- Reminder: lots of different kinds of distance measures!

image from Grootendorst post on distance metrics

Our approach in this class: exploratory data analysis, visualization and geometric perspectives

- From Tukey (1977, p. vi):

exploratory data analysis...looking at data to see what it seems to say

"The greatest value of a picture is when it forces us to notice what we never expected to see"

But beware: the curse of dimensionality" and high-dimensional spaces

MacKay (2003, p. 363-364) on the perils of importance sampling in high-dimensional spaces (h/t: Vehtari blog post.

See also 3Blue1Brown lesson How to lie with visual proofs

Curse of dimensionality visualization: https://online.datasciencedojo.com/blogs/curse-of-dimensionality-python

tSNE visualizations: https://ai.googleblog.com/2018/06/realtime-tsne-visualizations-with.html

Geometric review of linear algebra

Dimensions

- Interlude: what is a real number? Are phonetic spaces really real vector spaces?

What is a dimension?

Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions

Chapter 3 of 3 Blue 1 Brown: https://www.3blue1brown.com/lessons/span

- Go over animations, including subspace animation and connections to, e.g., missing a vector in your list (dimensionality reduction, linear inseparability vs. linear separability, )

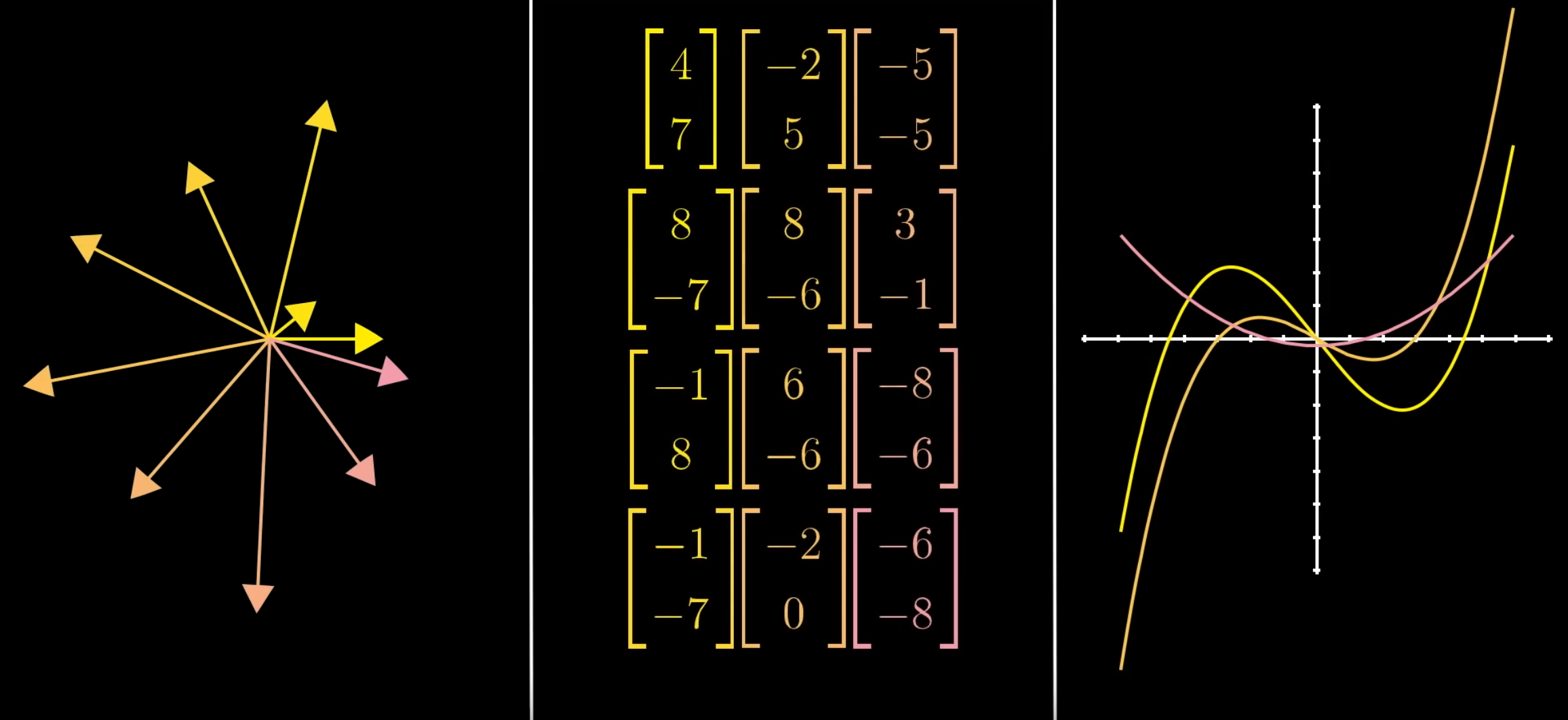

Key concepts leading up to dimension...(definitions adapted from Axler book)

Linear combinations : A linear combination of a list

the form

where

- The set of all linear combinations of a list of vectors

- A list of vectors

- A basis of

- The dimension of a finite-dimensional vector space is the length of any basis of the vector space (any two bases of a finite-dimensional vector space have the same length).

What are the dimensions of spaces when we have timecourses?

- Pointwise formant spaces vs. formant trajectory spaces: Stanley blog post example

- Neural representations: still a time course! https://huggingface.co/spaces/GroNLP/neural-acoustic-distance

Geometry and generalization

- Let's assume a fixed vector space and think about learning within it (later we will think about transformations, and then changing spaces, etc.)

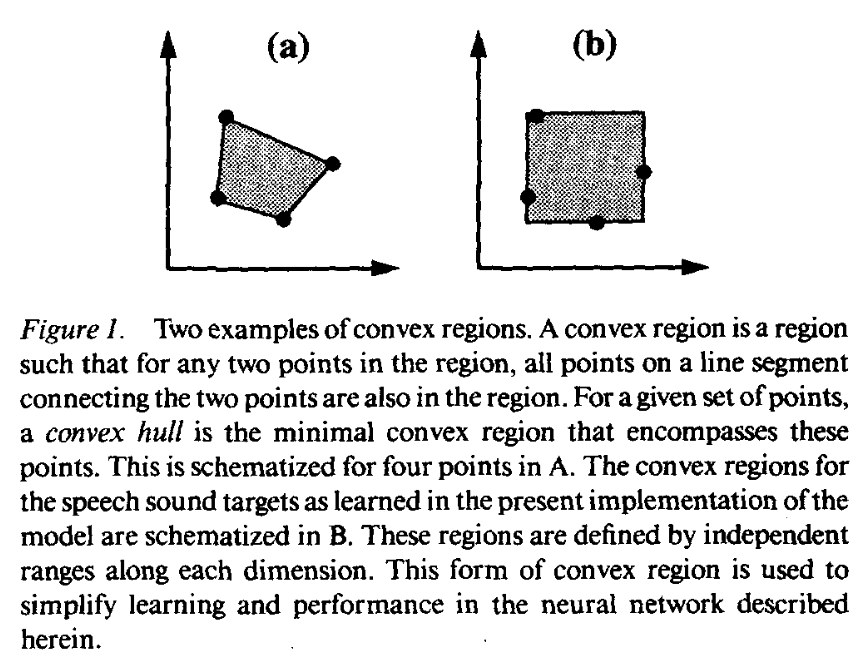

- What is a convex region?

- Generalization of sound categories via babbling: Günther (1995): "To explain how infants learn language-specific variability limits, speech sound targets take the form of convex regions, rather than points, in orosensory coordinates."

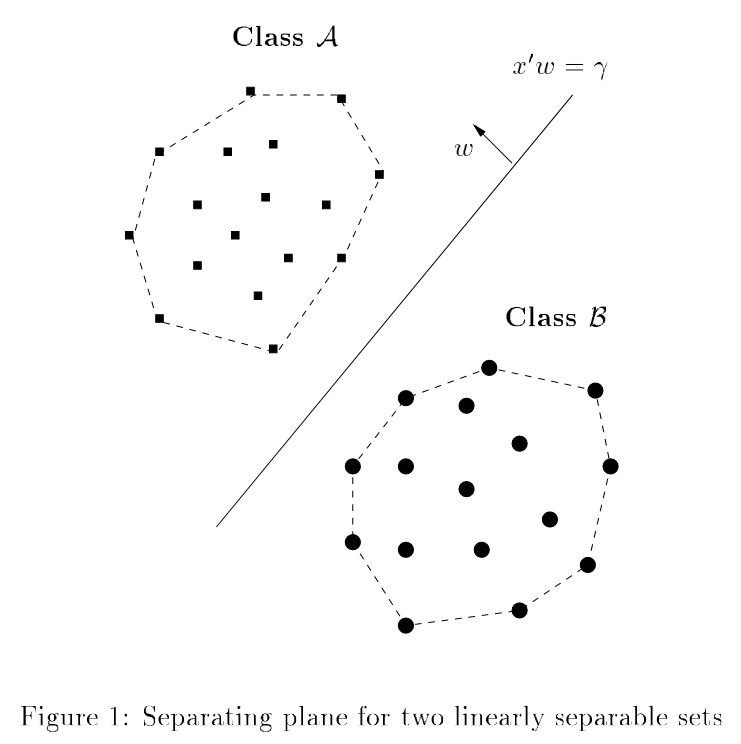

Convexity and linear separability: What can a perceptron learn? Training a perceptron corresponds to finding a separating (hyper)plane between two concepts/classes.

What is a convex hull of some set of points

If the convex hulls of

Why do we care about linear separability?

- Lots of work in cognitive psychology investigating and/or assuming that linearly separable concepts are "easier to learn", or that linearly separable classes are "natural" properties/concepts, etc. see for instance Gärdenfors (2004, Chs. 3, 4)

- Machine learning: classic problem of linearly separable vs. linearly inseparable and development of learning algorithms, relevance for the complexity of your classifier, e.g., linear discriminant analysis vs. quadratic, etc.

- Note that the idea of learning the separating hyperplane and discriminating classes is different from a "generative" approach.

Note that of course whether or not two classes are linearly separable depend on the space that the examples are defined in! (coming up later in course)

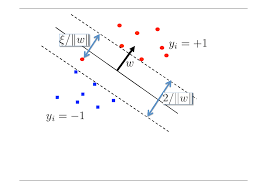

Generalization to maximum-margin classifier (support vector machines)

- The idea of critical examples: support vectors, that limit the width of the margin between classes (the other examples don't matter for determining the optimal separating hyperplane!)

Prep for Week 2: transformations!

Pick one of the topics to read about and be responsible for saying something about on Thursday:

Vowel normalization, vocal tract normalization, etc.

- Vowel normalization bibliography up to 2011: http://lingtools.uoregon.edu/norm/biblio1.php

- (also see NORM suite)

F0 normalization, pitch range, etc.

- Various Rose papers, Chao 5 pt scale, Zimman

Centering in regression and standardization in machine learning, computation

Time normalization? Pi-gestures, dynamic time warping, speech rate...

Further reading

Conceptual spaces and learning concepts: Anthony and Biggs (1992) Ch. 1 (in

readings/)Vector spaces: Axler (2015) Ch. 1 (in

readings/)Why thinking about dimensions is important for thinking about sound categories: Yu (2017) introduction

Input vs. intake: Lidz & Gagliardi (2015): https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-linguist-030514-125236

Geometry in learning: https://homepages.rpi.edu/~bennek/svmdt.ps, https://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/~cvrg/bennett00duality.pdf

Geometrical approaches to statistical analysis: https://scottroy.github.io/geometric-interpretations-of-linear-regression-and-ANOVA.html